Fellow Nurses Africa News

Special Report | 30 November 2025

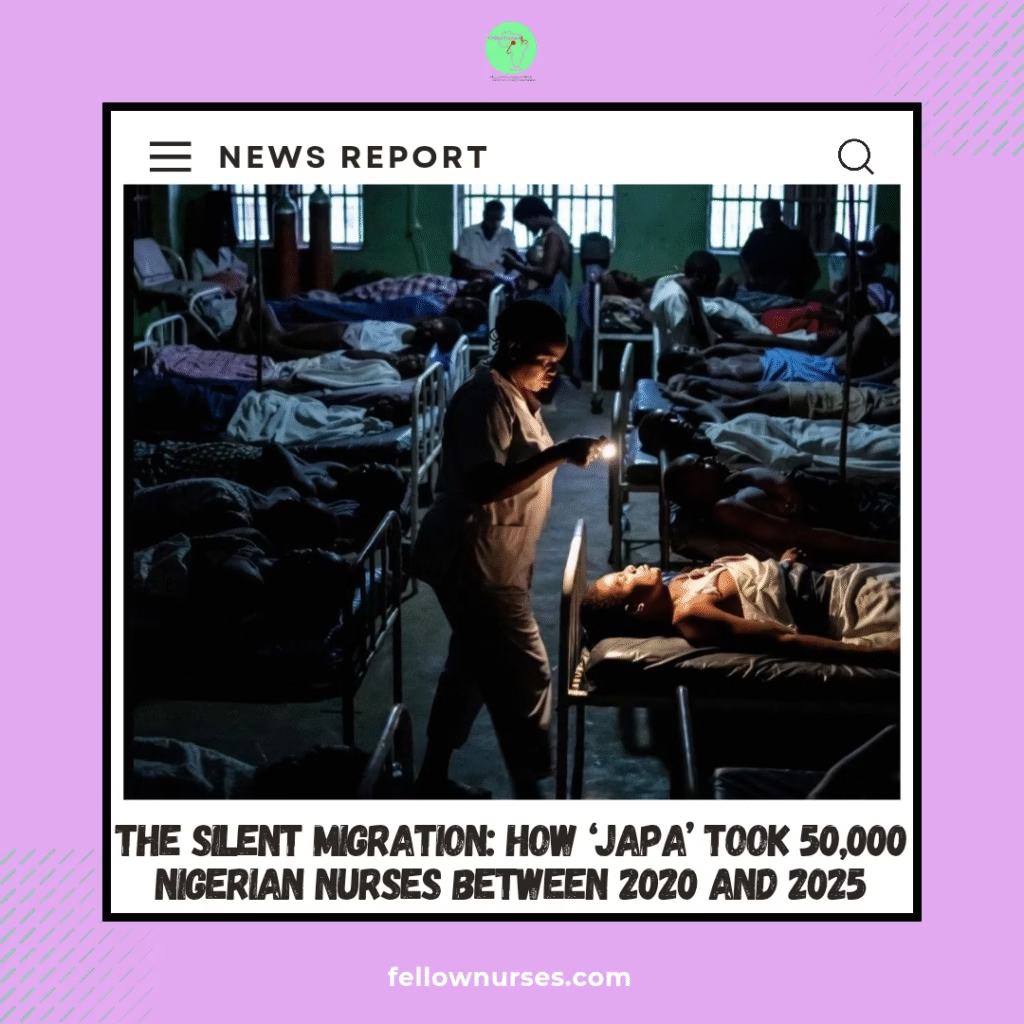

The Silent Migration: How ‘Japa’ Took 50,000 Nigerian Nurses Between 2020 and 2025

PNO Adaora Nwosu still wakes at 3 a.m. hearing the alarm that never came.

She was the only registered nurse on duty that night in the adult emergency ward of a teaching hospital in south-east Nigeria. Forty-two patients, one working manual blood-pressure cuff, no oxygen cylinders with functioning regulators, one bag of intravenous fluids left in the entire unit.

A man in his forties arrived in cardiac arrest. There was no single defibrillator. Adaora started CPR alone, then begged two ward attendants to take turns. After forty minutes her arms gave out. The patient died on the bare floor, not even a trolley.

👉 Join our Whatsapp channel Here

“That was the night my body decided for me,” she says. “I could not carry another death I could have prevented if only we had the basics.”

She is one of 50,000.

Between 2020 and 2025, Nigeria lost the equivalent of one in every four nurses it trained, according to estimates from the Nursing and Midwifery Council of Nigeria (NMCN) and the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC). The United Kingdom alone registered an estimate of 15,000 Nigerian-trained nurses during that period — peaking at 13,656 in the 2023–2024 financial year before new visa rules slowed the flow to a trickle of 2,363 in 2024–2025.

The breaking point

The nurses who left describe a form of slow violence, compounded by systemic failures documented in multiple studies:

- Workload that killed both patients and morale — one nurse responsible for 30–40 patients on a medical ward, far exceeding the World Health Organization’s recommended ratio of one nurse per six patients in general wards; in intensive care, one nurse to eight ventilated patients when international standards demand one-to-one or one-to-two.

- Stress that became physical illness — chronic hypertension, panic attacks on the way to work, nurses collapsing in the car park from exhaustion after 72-hour stretches with no relief, contributing to a nurse-to-population ratio of just 1.68 per 1,000 people as of 2022, well below the WHO’s minimum of 4.45.

- Patient deaths that were no longer surprises — sepsis because the last bag of antibiotics finished two days earlier; hypoglycaemic coma because the ward could not afford glucometer strips; postpartum haemorrhage because the only available oxytocin was expired — amid a national maternal mortality ratio of 1,047 per 100,000 live births in 2023, a 14% rise from 917 in 2017.

- The constant apology — “Sorry, no oxygen.” “Sorry, no blood.” “Sorry, the doctor is coming but the road is blocked.” “Sorry, we have no gloves today.”

- Moral injury — knowing exactly what needed to be done, having the skill to do it, but being powerless because the system had nothing to offer except your bare hands and a prayer.

Sister Emmanuel in Jos once calculated that in a single month he personally witnessed 28 preventable deaths.

“I stopped counting after that,” he says. “It was the only way to stay sane enough to come back the next day.”

Nurse Tunde in Port Harcourt kept a private diary of the patients he believed died because he was simply too tired to notice the early warning signs — the subtle drop in urine output, the slight confusion that signalled sepsis.

“I was scared to open the diary again,” he says. “I was scared of the number.”

👉 Join our Whatsapp channel Here

These burdens were exacerbated by starting salaries of ₦110,000–₦170,000 net per month in federal hospitals — equivalent to about ₦1.3–2 million annually — often eroded by months-long arrears and out-of-pocket costs for essentials like gloves and fuel for generators. In contrast, the same nurses now earn £29,000–£38,000 a year abroad.

Security threats added another layer: between July 2024 and June 2025 alone, at least 4,722 people were kidnapped in 997 incidents nationwide, including healthcare workers en route to rural postings, with over 762 killed and ransoms totaling nearly $1.7 million demanded.

The quiet decision

One morning, after another 36-hour shift with no sleep, Sister Adaora sat in the nurses’ station and wrote her resignation letter on the back of a drug chart.

She did not cry. She was too tired for tears.

Three months later she landed at Glasgow airport. On her first night shift in the NHS she cared for six patients.

“I kept waiting for the other thirty-four to arrive,” she says. “When they never did, I sat down in the corridor and cried for the first time in years — not from exhaustion, but from relief.”

The wards back home are still waiting.

👉 Join our Whatsapp channel Here

Fellow Nurses Africa is the independent voice of African nursing, we educate, inform and support nurses across Africa